Glenn Ellmers, Doug Wilson, and Theonomy

Glenn Ellmers, writing for The Federalist, recently tackled the clash between Hillsdale College’s Larry Arnn and CREC pastor Doug Wilson, the latter of CNN infamy. Ellmers starts by citing Arnn’s claim that a “Christian nation” is impossible but quickly pivots to Wilson’s views, concluding that Wilson’s apparent demand that “public officials proclaim their personal faith in Christ is neither wise, nor moral, nor American, nor Christian.”

Ellmers likely refers to Wilson’s oft-stated wish to enshrine the Apostles’ Creed in the Constitution – a notion we’ll dissect shortly. But first, let’s unpack Ellmers’ take on Wilson’s core arguments: (1) moral judgments require a transcendent grounding, and (2) all laws carry moral weight. Ellmers nods in agreement but balks at Wilson’s reasoning, particularly his insistence that morality must be “grounded in the nature and character of the living God.” Ellmers cries foul, claiming this rejects natural law and Scripture itself, citing Deuteronomy 4:5-7 and Romans 2:14-15, which suggest Gentiles can grasp justice without revelation. To Wilson’s mantra, “Christ or chaos,” Ellmers retorts that this denies the biblical principle of natural law.

But Wilson isn’t saying pagans are clueless about right and wrong. A pagan can sense murder is evil without cracking open a Bible. But Wilson’s point is sharper: any claim to objective morality collapses without the Christian God as its anchor. Without Christ, morality is just hot air – arbitrary claims. In this, Wilson is right: it’s Christ or chaos. Ellmers’ appeal to natural law dodges the deeper issue. Natural law, accessible to human reason, still requires a divine source to be coherent. Romans 2:14-15 doesn’t let pagans off the hook; it shows they’re accountable to the work of God’s law written on their hearts, not some autonomous moral code.

Ellmers further faults Wilson for asserting that government can’t act morally unless it explicitly bases laws on the Gospel, calling this a repudiation of the American founders’ tradition of rational justice. He writes, “For the founders, the laws of nature and of nature’s God – accessible to all rational humans – supply the sufficient ground for republican morality necessary to make self-government work.” Ellmers is hung up on epistemology – how we know what’s just – while ignoring the philosophical grounding of morality itself. Wilson’s point stands: laws enforce morality, and that morality must trace back to God, not man’s fickle reason.

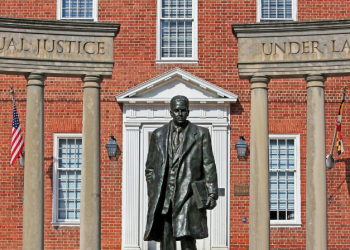

But here’s where we part ways with both Ellmers and Wilson. The elephant in the room isn’t whether officials should recite the Apostles’ Creed or if pagans can intuit morality. It’s this gem from Ellmers: “The government would pass fair and reasonable laws only on the basis of man’s rational understanding of justice based on human nature.” Fair and reasonable? By whose standard? Ellmers’ vague appeal to human nature is a house of cards, collapsing under the weight of sin-soaked reasoning. If a government adopted the Bible as its lawbook, with judges adjudicating cases per God’s perfect law (Psalm 19:7), would Ellmers call that “fair and reasonable”? Or would he clutch his pearls, fearing a theocratic boogeyman?

Wilson, for all his fire, stumbles here too. His push for the Apostles’ Creed in the Constitution is a distraction. In terms of practical outworking, I think the difference between Wilson’s Christianized republicanism and the standard statist fare might be paper-thin. Wilson doesn’t challenge the legislative machine that churns out endless laws, ignoring God’s law in favor of human edicts. This is the fatal flaw. The U.S. system, with its Article I legislature, breeds injustice by design. God’s form – judges applying His law (Deuteronomy 16:18-20) – establishes justice; man’s form, whether draped in Christian rhetoric or not, breeds chaos.

The real question isn’t whether pagans grasp morality or whether officials should salute the Creed. It’s this: what is justice, and how do we establish it? This is our task: “Justice, and only justice, you shall follow” (Deuteronomy 16:20).

God’s law, not natural law or constitutional creeds, is the blueprint. Wilson’s flirtation with a Christianized Constitution keeps one foot in the statist camp, while Ellmers’ natural law obsession leans on human reason over divine command. Both miss the mark. Theonomy demands we ditch man-made systems and embrace God’s order, where judges wield His law to deliver justice, not just for a generation, but for all time.